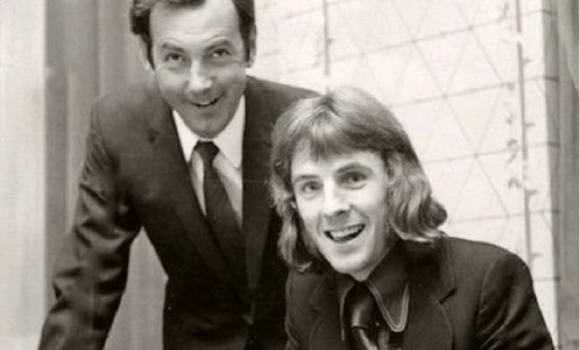

Gordon Jago: Leading from the front — Column Wednesday, 6th Jan 2021 13:24 by Simon Dorset On the fiftieth anniversary of Gordon Jago taking charge of Queens Park Rangers for the first time, AKUTR’s columnist Simon Dorset reflects on his often overlooked transformative influence on our club and the wider sport. Today marks the 50th anniversary of when Gordon Harold Jago MBE took over the reins at QPR. While he is still lauded in Shepherds Bush for being the founding architect of our greatest ever team, his influence over the development of “soccer” in the United States of America is immeasurable. As coach of the Baltimore Bays in the late 60’s he was at the forefront of the North American Soccer League. Returning to the States after enjoying success managing both QPR and Millwall, he was coach at the Tampa Bay Rowdies during the sports explosion a decade later. Following a total of 11 years in charge of the indoor soccer side Dallas Sidekicks, he was appointed commissioner of the World Indoor Soccer League before accepting the role of exec director of the Dallas Cup, which he built into one of the most prestigious youth tournaments in the world. Jago is one of the sport’s greatest pioneers, with every new venture he broke new ground and set new standards. Early daysGordon Jago was born in Poplar on October 22, 1932, and raised in East London. To escape the blitz, Jago’s parents moved their family out of the capital city into the Kent suburb of Welling. The young inside forward rapidly progressed through the local schoolboy ranks playing for North Kent Schools, Kent Schools and London County Schools. Jago’s performances for those schoolboy representative sides brought him to the attention of Dulwich Hamlet. His leadership qualities were obvious from an early age and, just as he’d been made captain of each of those teams, Hamlet immediately installed him as the captain of their junior team at the start of the 1949/50 season. While at Champion Hill he was selected to play for Surrey County Schoolboys. At the trials one of the coaches instructed Jago to play centre half because he was the tallest boy there; he remained in this new position for the rest of his career. It was not long before Jago caught the eye of Charlton Athletic’s long-serving manager Jimmy Seed and he signed amateur terms for the Addicks in 1952 without ever featuring in a first team match for Dulwich Hamlet. However, Charlton had not been Jago’s first choice. He had also attracted an offer from Spurs, but a bus strike on the day he was due to sign for them meant that he opted for the shorter journey to The Valley instead. He was immediately sent out on to Maidstone United on loan and while playing for The Stones he had the honour of captaining the England youth team. With National Service beckoning, Jago signed part-time professional terms with Charlton who, in turn, arranged for his national service to be with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps in Portsmouth enabling him to return home to play at weekends.

In common with many other of the best managers, Jago had an unremarkable playing career. He spent ten years at Charlton and played almost 150 league matches, scoring just one goal. In his early years at Charlton, Jago cities Benny Fenton as being particularly supportive. Fenton, who was Charlton’s captain at that time, would keep continually talking to him throughout every match and would always offer him a match post-mortem; a practice that Jago adopted into his own philosophy. Frustrated by the poor standard of coaching at Charlton, he took his preliminary coaching badge while still young and helped out at the FA as a staff coach instructing other coaches at Lilleshall, while exchanging ideas with men such as Walter Winterbottom, Ron Greenwood and Jimmy Hill. A kick in the eye he suffered in a match against Middlesbrough provided him with the impetus to move into full time coaching. His appetite for playing waned after being told by the medical staff at Moorfields Hospital that a blood clot caused by that kick could have left him blind and so, despite being only 28, he resolved to quit. Charlton retained his registration for a further season, but then he was free. Jago decided to accept the offer to become Eastbourne United’s manager in preference to becoming Jimmy Hill’s assistant at Coventry City which allowed him to continue to work for the FA and take youth and amateur players on tours. He approached his first managerial appointment with the aim to “provide all the things I never had as a player and that I thought we ought to have had”. Revelling in his first chance to put his belief that the foundation of a successful team was ten outfield players who could put his control, pass and move mantra into practise, Jago’s embryonic methods quickly bore fruit as Eastbourne United becoming serial winners of the Sussex Senior Challenge Cup until the lure of replacing Dave Sexton as coach at Fulham in Division 1 proved irresistible. While at Craven Cottage, Jago was presented with the most important, but unexpected, opportunity of his life. As part of the preparations for the launch of the North American Soccer League, Fulham flew out to Oakland in April 1967 to play a midweek match against Budapest Honvéd FC, igniting a mutual love affair with America which is still flourishing. American revolutionIn December 1967, the United Soccer Association and the National Professional Soccer League merged to form the North American Soccer League (NASL) and looked to the outside world to enhance it. Jago had made such a strong impression in his very brief visit that he was contacted by a number of NASL clubs before agreeing to become the new coach for the Baltimore Bays, who had won the Eastern Division but lost to the Oakland Clippers in the two-legged Championship Final in the final season of the NPSL. The reliance on expensive, imported talent was a sadly flawed business model which left the clubs hopelessly exposed when the expected crowds failed to materialise. At the end of the first season, CBS withdrew their television contract resulting in 12 of the 17 teams folding. At a meeting of the remaining team owners in Dallas, Jerold Hoffberger, the Baltimore Orioles majority shareholder who, in turn, owned the Baltimore Bays, committed to honour their obligations to the NASL for a second season but advised the others, in confidence, of their intention to shut down at its conclusion; Hoffberger’s overriding objective was to avoid any adverse publicity for his baseball team. In what he described as his hardest job, Jago was instructed to close down the franchise as quietly as possible. To minimise their losses the Baltimore Bays not only switched their homes matches from the grandeur of the Orioles’ Memorial Stadium to Kirk Field, a high school football pitch, but also pared the playing staff to the bone. With no full-time players, Baltimore endured a horrendous season but one which was to stand Jago in good stead for the future as, unable to comment on club policy, he had little option but to grow a thick skin and learn how to ignore criticism. Jago’s talents didn’t go unnoticed in the United States. During his first season with Baltimore, he accepted an invitation from national team manager Phil Woosnam to be his assistant for the 1970 World Cup qualifying matches. Under their guidance, the United States won Group 1 in the CONCACAF (North, Central America and Caribbean) zone, but in early 1969 Woosnam resigned to take over as Commissioner of the ailing NASL. Jago was promoted to take over as the United States National Team Coach for their playoff matches. Unfortunately, Group 2 winners Haiti were too strong and won both legs of the semi-final. In those days, the only international matches that the United States played were World Cup qualifiers so, with no more matches scheduled for over 2 years, Jago’s involvement with their national team ended too. On his return to England in March 1970, chief scout Derek Healey alerted QPR’s hierarchy to Jago’s availability and he was appointed as club coach working under Les Allen at the end of the 1969/70 season. Results were disappointing the following season and, despite a resurgence in October, Jago decided that it would be in everyone’s best interests if he left and accepted an offer to become the head coach for the St Louis Stars in the NASL. However, before Jago could tender his resignation, chairman Jim Gregory sacked Les Allen and asked him to take over for a couple of weeks while he took stock of the situation. Jago made a couple of changes to the team improving results to such an extent that Gregory asked him to remain in place for the rest of the season. Jago was only too happy to oblige as he knew that that his potential job in St Louis didn’t require him until after the end of the English season. Building QPR greatnessAlmost before the ink was dry on the new three-year contract that Jago was awarded for steering QPR away from any relegation worries and into a mid-table finish in Division Two, Joe Mercer, the Manchester City manager, was trying to prise Rodney Marsh away. Jago insisted that Marsh’s outstanding form at the end of the previous season had secured him his new job and so, unsurprisingly, he dismissed Mercer’s enquiry outright. The following season was punctuated with repeated enquiries from Manchester City which, despite Marsh winning his first England cap after Jago persuaded Alf Ramsey to come to Loftus Road to watch him, eventually unsettled Marsh to such a degree that his performances became detrimental to the team. After Rangers dropped out of the promotion places Jago conceded that it would be in QPR’s best interests to sell Marsh, but not before Jim Gregory had negotiated the transfer fee up to £200,000 giving Jago additional capital with which to move his team onto the next level. Jago received an early indication of what life working for Jim Gregory held in store for him when he made his initial venture into the transfer market. Tipped off by Gillingham director and ITV’s chief football commentator Brian Moore that Luton were desperate to raise some funds, Jago struck a deal with their manager, Harry Haslam, to buy Don Givens for £40,000. Gregory immediately re-negotiated the transfer and was only satisfied once he’d managed to shave £2,000 0ff the price. Givens was an important signing in Jago’s bid to emulate the West German team that had so enthralled him at Wembley Stadium a few months earlier. That night, Helmut Schoen’s team ably led by Franz Beckenbauer, set the blueprint for how Jago wanted his teams to play. He knew that he needed players who possessed an excellent technique and were comfortable in possession of the ball to achieve this and the Republic of Ireland striker handsomely fulfilled that criteria and seamlessly blended into a team already boasting players of the quality of Venables, Francis, Busby and Clement.

Rangers solid, but unspectacular, start to the season prompted Jago to suggest signing a target he’d identified in the penultimate match of the previous season. Despite Carlisle being comfortably beaten 3-0, their star player had made a very favourable impression on the QPR hierarchy, so when Jago recommended signing Stan Bowles, Gregory could not have been more supportive. He immediately met Carlisle’s asking price, personal terms were agreed and the following Saturday QPR unleashed their new number ten against Nottingham Forest. It took Bowles just two minutes to start to exhume the spectre of Rodney Marsh when his left-wing cross was headed home by Givens. Bowles’ first ever QPR goal followed shortly afterwards. Barely a month later, Jago was forced to return to the transfer market after Martyn Busby, believed by some to be a better prospect than Gerry Francis, suffered a potentially career ending broken leg against Fulham at Craven Cottage. Jago knew that it was imperative to supplement his small squad if Rangers were to maintain their promotion aspirations, but was stunned when Gregory suggested Burnley’s England under-23 international Dave Thomas. Thomas, who had been hailed by Don Revie as the finest young player in Europe, perfectly fulfilled Gregory’s criteria of only signing players who were not only capable of helping Rangers win promotion but also being good enough to keep them in the top division. Gregory struck a deal with Burnley chairman Bob Lord and Thomas was on his way to Loftus Road. Sadly, Busby was never able to fulfil his potential after that injury.

Still haunted by the appalling training methods he suffered at Charlton, Jago took the innovative step of employing sprinter Ron Jones as the club’s fitness coach. Jones, who was a member of the British team that set a new world record in the 4x110 yards relay in 1963 at the White City Stadium and was appointed as Britain’s Athletics Team Captain at the 1968 Mexico Olympics, introduced some revolutionary drills and practices into his sessions, many of which Terry Venables continued to use throughout his managerial career. Richly benefiting from increased fitness levels and bolstered by his new strike force, Jago’s team laid siege to their opponents’ defences with a breath-taking style and panache befitting their manager’s vision born that night at Wembley Stadium. The precision of their control, crispness of their passing, fluidity of their movement and the freedom afforded to the players was totally alien to the English game. Rangers, who had no concept of game management and rarely eased up when ahead, were comfortably the division’s leading goal scorers; Givens the division’s individual highest scorer with 23 goals with Bowles not far behind him with 17. Their free-flowing, exhilarating football was duly rewarded with promotion to the First Division with four matches still to play.

Jago was confident in his vision of how football should be played and his team’s ability to continue to deliver it at the higher level, but he knew that he still needed his “Beckenbauer”, a player who could carry the ball out from defence and link effortlessly with his midfield. When it became known that Arsenal were looking to sell Frank McLintock, Jago wasted no time in persuading him to come to Loftus Road. After gently acclimatising to life in the top division, Rangers recovered from the set back of losing coach Bobby Campbell, who was disillusioned by not receiving the correct pay rise he was due on achieving promotion, to claim some notable scalps, including both Manchester clubs, Arsenal, Spurs and Chelsea, on their way to finishing as London’s top side. The style and purpose with which they played not only won them The Sun’s award for being the most attractive team in the top division, but also prompted the FA to interview Jago for the vacant England manager’s job after they had sacked Sir Alf Ramsey. Jago and his old friend Bobby Robson, who’d been captain at Fulham when he’d been coach, were the main candidates until Don Revie declared his interest in the role.

While Jago was quietly relieved at not being offered the England job, he was still disappointed about not being allowed to take the England U-23s on a short European tour that summer. Gregory had instructed him to turn down the approach made by Sir Alf Ramsey in April that year because the dates clashed with QPR’s summer trip to Jamaica which had been arranged as a reward for their successful season. As that trip drew near, Gregory informed Jago that he was not to go to Jamaica but remain at home in case any potential transfers arose, but then promptly went away on holiday himself and left a message for Jago with his son informing him that there were no funds available. Jago, whose frustration with the manner in which Gregory conducted himself, interfered in team matters and dictated the club’s transfer policy had reached breaking point, saw little option other than to resign. On his return, Gregory asked Jago to reconsider his decision offering him various assurances regarding the future while at the same time telling Jago that he’d arranged to sign Dave Webb from Chelsea. Jago tentatively agreed but, with Gregory questioning virtually every decision he took, quit again on 27th September 1974, the day he describes as the saddest day of his footballing career. Post QPRWhile mulling over an offer to join Ron Greenwood at West Ham until the right opportunity presented itself, Jago received several phone calls from Brian Moore on behalf of Herbert Burnige who was the chairman at Millwall. Moore eventually convinced Jago to suspend his reservations regarding the reputation of Millwall’s supporters and to meet with Burnige and was unexpectedly impressed by him to such a degree that, despite having a number of significant options available to him, Jago decided to accept the role as Millwall’s new manager replacing Benny Fenton who had been his captain at Charlton when Jago broke into their first team. Whereas his ideas and methods had been welcomed and embraced at QPR, they met with considerable resistance from the senior Millwall players. Jago wanted to organise extra coaching sessions to work on their organisation and to develop some new set-piece routines in their battle against relegation, but few showed any inclination to attend. He was left with little alternative than to swiftly move on those players who were not committed to the battle they faced enabling him to bring in some new faces including Tony Hazell who was no longer considered a first team player at QPR. However, Jago was unable to prevent Millwall sliding down into Division Three. Jago set about changing Millwall’s reputation and standing in the game. Cosmetic changes to improve their facilities, such as painting and tiling, were easy to affect, but getting to grips with the club’s hooligan culture was far more problematical. The unwillingness of sections of the club’s fanbase to even meet with him led him to accept an invitation to fly to the USA to meet with the United States Soccer Federation with a view to becoming their national team coach. Heeding the advice of his former colleague Phil Woosnam among others, Jago eventually declined the role to continue his work at Millwall. Although Millwall had been inconsistent for most of the 1975/76 season, a powerful 15 match unbeaten run almost mirroring the one undertaken by the QPR team he’d left behind, saw them surge into the promotion places. In an uncanny coincidence both teams had to wait for their challengers to finish their matches before knowing if they’d been successful. In QPR’s case sadly not but, when Crystal Palace failed to beat Chesterfield, Millwall’s promotion back to Division 2 was confirmed. Following a season of consolidation during which Jago continued to make gradual improvements in both the club’s facilities and in the behaviour of some of the club’s supporters, he was contacted by the BBC who wanted to make a documentary for Panorama charting their efforts in this direction. Keen to let the public at large see the progress that they’d made, he agreed to allow the cameras into Cold Blow Lane. Jago was mortified when he saw the final programme which solely focused on the hooligans’ behaviour at its worst and unfounded links to fascism and the National Front. Feeling that all of their hard work had been instantly undone and that he’d let the club down, he resigned. Back in 1974, when George Strawbridge purchased a NASL expansion franchise to be based in Tampa, Florida he immediately offered Jago the manager’s role. Jago, who was still enjoying life at QPR declined the offer and did so again when it was repeated in 1977 while he was on holiday in the area. A year later, following Jago’s resignation from Millwall, Strawbridge finally got his man offering him an escape from his frustrations in London, but Jago’s influence at Millwall was felt for many years after he’d left thanks to the youth policy that he had instigated utilising the burgeoning coaching skills of Argentinean Oscar Fulloné Arce and the experienced scouting of Derek Healy. While Jago wasn’t around to enjoy their FA Youth Cup victory in 1978/79, his involvement in its inception ignited a passion in him which would become more and more prominent during the rest of his career. At the Tampa Bay Rowdies Jago was reunited with Rodney Marsh. With any lingering animosity between the two put aside, Marsh was instrumental in transforming the team’s stuttering start to the season. An outstanding run of 13 wins from their last 17 matches saw them climb to 2nd place in the American Conference Eastern Division, level on points with the New England Tea Men, but behind due to having won one match fewer. Further victories in the playoffs against the Chicago Sting, the San Diego Sockers and their arch rivals the Fort Lauderdale Strikers saw Jago’s team through to the Soccer Bowl in his first season as manager. Soccer Bowl ’78 was played in front of a then record crowd of 74,901 supporters at the Giants Stadium in New Jersey. The Rowdies’ opponents were the New York Cosmos who were able to field such illustrious names as Franz Beckenbauer, Carlos Alberto and Giorgio Chinaglia. To Jago’s surprise, Marsh declared himself unfit on the morning of the match as a result of a gashed shin he’d suffered against Fort Lauderdale. Two goals from former Manchester City forward Dennis Tueart and a penalty from Chinaglia eased Cosmos to a 3-1 win, with Brazilian Mirandinha replying for the Rowdies. The following season The Rowdies won the Eastern Division on their way to returning to the Soccer Bowl. Disappointingly they lost 2-1 to the Vancouver Whitecaps whose success was based upon legion of imported Englishmen such as Alan Ball, Trevor Whymark, Kevin Hector and Ray Lewington. Whymark scored both of the Whitecaps’ goals either side of an equaliser from Jan Van der Veen. This was Rodney Marsh’s last professional performance. He announced his impending retirement in the weeks leading up to the Soccer Bowl. Despite his lacklustre display, Marsh did little to hide his annoyance at being substituted as Tampa Bay chased an equaliser; he and Jago have not spoken since. The Rowdies had been playing Indoor Soccer for a few years over the winter break. These had generally been short tournaments or, at times, little more than exhibitions matches but, after years of lobbying by George Strawbridge, the NASL finally launched their Indoor Soccer League for the 1979-80 season. Jago was no stranger to indoor football having won the London Evening Standard 5-a-side tournament 3 times with QPR and he continued this success by steering the Rowdies to the final against the Memphis Rogues. Both teams won their home leg of the final, the Rowdies clinched the title in a 15 minutes play-off match. Ill-fated returnThe relentless schedule of non-stop football started to take its toll on Jago who freely admits that his judgement started to get impaired. In July 1982, after an amicable meeting with Strawbridge, he resigned. In his time at Tampa Bay, Jago had taken the club into the end of season play-offs in 4 of his five seasons as manager and also reached the Indoor Soccer final for a second time in the 1982/82 season. Jago was enjoying a break away from professional football when he received an unexpected invitation from Jim Gregory to return to QPR. After a successful spell as manager, Terry Venables had been lured away from Loftus Road by Barcelona and Gregory wanted to meet with Jago with a view to him returning. Jago made it clear that he had no interest in returning as manager but was interested in the marketing and promotional aspects of football and wanted to put into practice some of the ideas that he’d picked up in the States. Gregory immediately agreed and offered him the position of general manager. Jago flew back to Tampa to sell his home and make arrangements to return to London, however, a couple of days later, Jago received a phone call from Gregory’s son who told him the familiar tale that Gregory had gone on holiday and the job offer had been withdrawn. In 1984, Texan businessman Don Carter bought the bankrupt New Jersey Rockets, moved the Major Indoor Soccer League (MISL) franchise down to Dallas and renamed them the Sidekicks, and approached Jago to be their head coach. After initially declining, Jago finally accepted the role after a face to face meeting with Carter. Jago’s reservations about the team he’d been presented with proved to be well founded when they lost their first ten matches. In all, their first season only yielded 12 victories from 48 matches. As well as improving his squad over the closed season, Jago watched other indoor sports, such as ice hockey, to help him develop his ideas and evolve his tactics for the indoor arena. This paid an immediate dividend as the following season the Sidekicks won 25 of their 48 matches; Jago was named the MISL’s head coach of the year for masterminding this remarkable improvement. The Dallas Sidekicks story almost ended after just two seasons. Carter was set to file for bankruptcy when a consortium of the club’s supporters purchased the club off of him. Inspired by Tatu, a Brazilian player who Jago had initially bought from Sao Paulo for The Rowdies and then signed for the Sidekicks when the NASL folded in 1984, the Sidekicks clinched a place in the end of season playoffs after finishing third in the Eastern Division with 28 victories from their 48 matches. They beat the Baltimore Blast by three games to two in the best of five semi-final and then clinched the Eastern Division final by four games to one against the table topping Cleveland Force. On June 20, 1987, the Sidekicks went to Tacoma to play the deciding match in the best of seven games MISL Championship Final against the Stars who had won the Western Division final. 3 — 1 down with only 2 ½ minutes remaining, Jago’s gamble to replace his goalkeeper with an extra outfielder paid dividends when the Sidekicks scored twice in quick succession to force the match into overtime. In front of a record attendance of 21,728, Mark Karpun scored the deciding goal to win the trophy for Jago and the Sidekicks. The Sidekicks qualified for the post season playoffs in the next two seasons, but were not able to reach the Championship final again. Jago opted to step down and concentrate on the marketing aspects which continued to interest him. After a series of changes of owner, the Sidekicks were in danger of closing down when, in 1993, Don Carter stepped back into the picture. He immediately re-appointed Jago as head coach and switched allegiance to a breakaway league, the Continental Indoor Soccer League (CISL), for its inaugural season. After a steady start, the Sidekicks won 20 of their final 22 matches to secure a berth in the post-season playoffs where they beat the Monterrey La Raza in the semi-final and the San Diego Sockers in the final to be the first winners of the Lawrence Trophy. Jago was honoured with the Coach of the Year award and Tatu named the Most Valuable Player. The Sidekicks returned to the final the next season but were unable to repeat their triumph and remained competitive until the CISL closed in 1997 due to the franchise owners wanting to drive the conference in different directions. The Premier Soccer Alliance was formed in the place of the CISL. Some of the franchise owners asked Carter and his new partner Sonny Williams if they’d release Jago to be the league’s commissioner. Jago happily took this opportunity to retire allowing Tatu taking over as player/coach at the Sidekicks. He held the position for 3 years until the now renamed World Indoor Soccer League merged with the remaining franchises from the National Professional Soccer League; Jago willingly waived any claim he had to head up the new league to allow the commissioner of the NPSL to continue in his role. At the age of 70, and after dedicating the last 50 years of his life to professional football, Jago was looking forward to a well-deserved retirement. However, before he could even think about relaxing and enjoy the unknown concept of spare time, he was invited to become the executive director of the Dallas Cup. Since being founded in 1980, the Dallas Cup had been steadily enhancing its reputation as one of the premier youth team tournaments for teams from all around the world but, in the aftermath of the 9/11 atrocities, it was struggling to attract teams of the desired quality and was in danger of losing some of its status. Jago’s first call was to Newcastle United manager Bobby Robson who had been the captain of Fulham when Jago was their coach. Robson instantly agreed to send over his Under-19 team. Jago followed this up by securing some additional sponsorship through a contact he’d gained while coaching the Sidekicks and, in no time, the tournament’s immediate future was assured. Over the next few years Jago steadily rebuilt, and then enhanced, the tournaments reputation to such a degree that they had to relocate to the Toyota Stadium, home of FC Dallas, to accommodate the number of spectators who wanted to watch the matches. The first match he staged at their new home was between Under-18 teams from Manchester United and Real Madrid and attracted a live audience of over 17,000. The following season Dr Pepper became the event’s main sponsor, they have continued to be ever since. Jago’s outstanding work as the executive director of the Dallas Cup did not go unnoticed in his homeland and he was awarded the MBE for services to the promotion of international youth football in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list in June 2006. Perhaps the “peace” teams that he invited to the tournament were influential in this award. Most notable among these were a team comprising players from both Israel and Palestine and another from Northern Ireland containing both Protestants and Catholics. With the Dallas Cup firmly established as the World’s most prestigious youth tournament, Jago decided to step down as its executive director in 2012, although he still represents the tournament as an ambassador and special consultant. As a mark of respect and in gratitude for his services, the tournament’s top group was renamed in his honour — the Gordon Jago Super Group. The following year he was inducted into the Indoor Soccer Hall of Fame having previous been the inaugural member of the FC Dallas’ Walk of Fame, inducted into the Sidekicks Hall of Fame and was the recipient of the Disney Soccer Showcase Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010. Despite all his time he spent coaching in the United States and the success he achieved over there, Jago regards the 5 years he spent at QPR as the best time of his career. His efforts in transforming the club from one heavily dependent on Rodney Marsh to one capable of challenging for the top prize in English football must not be underestimated, the team that Dave Sexton took so close to winning the first Division had Jago’s hallmark stamped all over it. Gordon Jago rarely receives the acclaim he deserves on this side of the Atlantic Ocean. Throughout his career, whether as a quick-witted defender who successfully held his own against the best forwards of the day, an innovative coach whose teams always played entertaining football or a far-sighted administrator who worked tireless to achieve his aims, Jago led from the front. He remains a strongly principled man and one not frightened to challenge barriers, be they cultural, political or religious. He is also one who achieved the rarest of feats - he was never sacked from any coaching, managerial or administrative role. If you enjoy LoftforWords, please consider supporting the site through a subscription to our Patreon or tip us via PayPal Pictures — Chris Guy, club historian Action Images Please report offensive, libellous or inappropriate posts by using the links provided.

You need to login in order to post your comments |

Blogs 31 bloggersExeter City Polls |